RUSS 005 - Omeka Project - Sarthak Harjai

Russia's Regional Dominance: Expanding or Receding?

Introduction

Since the fall of the USSR, Russia has tried to retain its stature as a superpower in international affairs and as the dominant player in regional conflicts. Russia’s recent involvement in Belarus and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict are reflections of where Russia has succeeded in projecting its power domestically and where it has not. Russia’s response to regional conflicts highlight trends that stretch back over a longer period of time and affect Russia’s position in the region. Additionally, events in Belarus have received international attention that illustrate Russia’s ability to contend on the international stage as a world superpower.

Belarus and Russia

Context:

At the time of writing, the situation in Belarus is an evolving situation:

- President Alexander Lukashenko is still in power in Belarus.

- Russia is aiding Lukashenko’s regime through various means (more below).

- The United States (US), European Union (EU), and United Kingdom (UK) have all placed sanctions on key figures in the Belarussian leadership including Lukashenko.

- Widespread protests continue in many parts of Belarus with the largest being in the capital, Minsk.

Belarus: An illustration of Russian opportunism and fear:

Under Putin, the Russia seen for the past 20 years has been cunning and opportunistic, taking advantage of the perils of other countries to advance its own foreign policy aims. This is illustrated in Russia’s foreign policy direction with Belarus following a rigged election in August 2020 where Alexander Lukashenko retained power. Russia’s policy was to support Lukashenko’s government, in stark contrast to most other international powers that rejected recognising Lukashenko’s government as legitimate.

Asserting Russia’s position in the region is the first reason why Putin chose to support Lukashenko’s government. Approximately one month after the election, Putin had a meeting with Lukashenko to discuss "plans to further integrate their countries." Unification is not something most former Soviet states would willingly agree to. Indeed, before the protests, Belarus had increasingly gravitated towards the West, becoming closer to the EU. With the recent rigged election, however, Belarus lost any chance of cooperation with the West while under Lukashenko, and had no choice but to approach Russia. Russia could have chosen to ignore Belarus as a punishment for their foreign policy shift to be more in line with the EU. However, Putin saw Belarus’s weakened position as an opportunity to gain concessions from Belarus and bring it back within the Russian sphere of influence. Knowing that Lukashenko would have to realign his priorities to reflect Russia’s priorities, Putin provided aid to Lukashenko’s regime. From providing journalists to support understaffed propaganda machines in Minsk to possible military support to suppress protestors, Russia didn’t falter in supporting Lukashenko’s regime. While there is no official need for Belarus to be tied to Russia as a result of aid that Putin has provided during this tumultuous period for Lukashenko, there is also no choice. The rest of the international community has shunned Lukashenko’s legitimacy as leader of Belarus. While Russia’s aid has kept his regime afloat, it has also shut Lukashenko away from other foreign powers and as a result he must rely on Russia for any future international cooperation.

Putin’s opportunism in reclaiming Belarus as a part of Russia’s sphere of influence is by no means an isolated event. The 2014 Russian actions in Ukraine similarly portrayed Putin’s opportunistic tendency when it comes to matters within neighbouring regions. Russia took advantage of the situation to annex Crimea, a long-standing issue between Russia and Ukraine after the USSR transferred control of Crimea from the Russian Soviet Republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in 1954. This opportunism is a pattern. The pattern’s consequence is that Russia is likely to take part in any major developments in former Soviet states for it considers itself to be a leader in the region and continued engagement in the region even if it is viewed negatively by the international community will allow Russia to repeatedly reassert itself as the dominant power in the region.

The second reason for Russia’s involvement in Belarus is a fear of democratic ideology. Throughout the Cold War, the USSR exported its version of communism to counter Western nations’ export of democratic values. Although, Russia no longer actively engages in this behavior at the same level, it would still be strongly opposed to the export of democracy so close to its borders. Putin’s own regime in Russia may be more legitimate than Lukashenko’s after the election, but there is no question that Putin resorts to undemocratic methods to retain his power. If Belarus was to have a democratic revolution, Russians might start to question why they can’t have one, too.

This possibility is especially dangerous because of Belarus’s connections with Russia. Belarus is arguably the closest nation to Russia in terms of economic and cultural integration. This would provide more support for democratic revolutionists in Russia. A democratic revolution in Belarus would, for Russia, risk Russians asking if they could have a democratic revolution as well. It would bring democracy too close to Russia. While democracy in Russia wouldn’t necessarily be the end of the country, it would almost certainly be the end of Putin. Russia’s long-term trend to keep democracy away from its borders is due to Putin’s inherent nature as an autocratic leader. Democracy threatens his power. As long as he is in power, he will lead Russia to reject democracy both within Russia as well as within its neighbouring regions.

Opportunism to expand Russia’s sphere of influence and fear of democratic ideology both play a significant role in Russia and the Putin regime’s decision to be involved in Belarus.

How the situation at present reveals Russia and Belarus's intentions:

As the protests in Belarus have progressed, there has been a dialing down on the vocality of Russia’s support for Belarus in the last quarter of 2020. It still exists, to be sure, but it is not so prominent in Russian state media, and their initiatives are not announced with the grand show of support that they were at the start of the protests. This shift points to Russia’s support having become more docile in its vocality. Russia doesn’t see any reason for being vocal and further upsetting Belarussian protestors. For the most part, the situation is as stable as it can be for Russian-backed Lukashenko. Putin and Lukashenko are relying on tiring protestors out as the months go on. An example can be seen in article 3. In said article, Lukashenko and his security forces propose the use of deadlier force at protests on October 18. However, the protests that takes place that Sunday don’t see much of this force used. The following video shows these protests.

Lukashenko is trying to scare the population into giving in, yet he is unwilling to commit to further increase the violence used against protestors for fear of further angering them. Individually, protestors need to return to normality in their lives. They need to earn money in order to eat and feed their families. Hence, how long they are to stick with protests is unknown. For sure, neither Lukashenko’s grip on power, nor the protestors’ resolve can last forever. One of the two must give. The question is which?

What regimes like Lukashenko’s show, however, is that a single moment can erupt into a historical change. There is no going back from this election. If Lukashenko is to hold onto power, he will have to continue to play into Russia and Putin’s hands. For the time being, this looks like a success story for Putin. He has kept democracy away from his borders and gained considerable leverage over a former Soviet state, Belarus, and its leader.

A closer look at sanctions on Belarus and their implication for Russia:

The EU, UK, and US have all implemented sanctions on key leadership figures in Belarus rather than on the economy as a whole. They don’t impact or intend to impact the Belarussian economy at large. Instead, they want to financially hurt those that are in positions of power in Belarus and are suspected of helping with election interference. It’s largely unknown to what extent, Belarussian leaders hold assets across the EU, America, or other Western countries. It would be reasonable to suggest the sanctions would have some impact, but since the impact is hard to measure, it isn’t always effective or reliable. Nonetheless, Russia and, more importantly, Putin, have taken note of the sanctions. Besides dismissing the sanctions, Russia hasn’t taken any major steps to counteract the sanctions on key Belarusian figures. This decision is a reflection on Russia’s position as a world power. Russia is aware that it doesn’t have the same say on the world stage that it did in the twentieth century. Russia’s indifference to the sanctions is a very small piece of a larger trend: Russia’s waning international influence and Putin’s cognisense of this new reality.

Azerbaijan and Armenia

Russia’s initial hesitation in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict:

At the start of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Putin called for “an end to hostilities in the zone of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.” Article 5 specifically mentions diplomatic efforts as being stepped up. At the time the article was written, Russian involvement, even after stepping up efforts, was at a level that was far lower than expected. This fact was highly unusual for Russia, which likes to take an involved and harsh approach to the countries that are its immediate neighbours or former Soviet states. Multiple explanations present themselves: Turkey and its relations to Russia, the COVID-19 pandemic, and ongoing conflicts.

The first one is perhaps the most concerning. Turkey and Russia have been on negative terms for some time. Turkey has supported Azerbaijan in this conflict — a move that can be viewed as an expansion of their foreign influence. Russia likes to be the dominant player in its backyard. As such, one could imagine the state wouldn’t take kindly to this kind of behavior. However, article 5 points out that even after a few weeks, Russia had been unwilling to commit more than just words to the conflict. Having a defense agreement with Armenia as well as bases there, it could have been expected of Russia to support Armenia faster and with greater force. Russia’s disinclination to join the conflict as quickly as it may have done in the past is another marker of its waning influence as an international power. Worryingly for Russia, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is not just of international but also of domestic importance. The long-term trend of Russia’s waning international influence is not a result of Putin’s willingness to pull back from involvement in the region, rather it is the trend can be viewed as a symptom of different issues.

One such issue that has recently emerged is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Russia’s military and state structures likely find themselves stretched thin due to the pandemic’s effect on them. However, this raises questions about Russia’s current military readiness. If Russia is unwilling to engage in proxy wars with countries like Turkey, how can Russia claim to be as internationally relevant as the US, EU, or China?

This may not be the only factor. Russia is also involved in other conflicts. From continued involvement in Ukraine to possibly preparing for a flare up in Belarus, these conflicts may be using up Russian state resources which makes Russia unwilling to commit to another conflict. This highlights another worrying trend for Russia. It has involved itself in many regional conflicts over the last two decades. It’s initial unwillingness to do so in Nagorno-Karabakh shows that these conflicts are expensive for Russia to engage in. If this trend continues, there may be less Russian involvement in regional affairs.

Turkey’s involvement:

Nonetheless, at the end of the day, it is Russia that has brokered the ceasefire and committed to put almost 2,000 troops in the region for peace-keeping missions. This is one of Russia’s biggest active foreign peacekeeping missions. Russian troops can be seen arriving in Nagorno-Karabakh for peacekeeping in the following video.

Russia’s hesitation to be involved initially was largely broken by their unwillingness to cede influence over former Soviet nations to Turkey, a country with whom Russia is not on the best of terms. This Russian-backed end to the conflict is also what the region generally expected of the situation. However, it is starkly different from other instances of Russia exerting influence in its neighbouring regions due to Turkey’s involvement.

For one, it is clear that Azerbaijan is closer to Turkey after this conflict. It wants to see a Turkish presence as a part of the Russian-brokered ceasefire deal or some extension of it. Azerbaijan’s reasoning is clear. Turkish backing has helped them gain the edge in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and they’d like to retain that edge for the future and for any ceasefire settlements. Turkey’s intentions are also clear, they want a foothold in the region. This is part of an ongoing small scale feud between Russia and Turkey. Russia’s size and military power keeps Turkey from directly engaging. Thus, most conflicts can be expected to be in a proxy form such as exerting influence over nations which is what has been done via Turkish help to Azerbaijan for this conflict.

Turkey’s involvement in the crisis has likely been viewed by Russia as Turkey trying to gain influence in Russia’s backyard. This Kremlin-backed ceasefire is both a soft and hard response to that influence.

Conclusion

In Belarus and Nagorno-Karabakh, Putin has been able to secure foreign policy victories by expanding his sphere of influence and reasserting Russia’s claim to be the dominant power in the region. The underlying reasons for Russia’s involvement in events within Russia’s neighbouring regions is to assert Russian dominance and retain Russia’s position as the dominant player in the region.

However, upon closer inspection, the events in both Belarus and Nagorno-Karabakh show that there were a lot of bumps on Putin’s path to foreign policy success in both cases.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia’s involvement was delayed. This fact is a consequence of the regime's unwillingness to commit unnecessary resources to conflicts. As discussed earlier, over the last decade there has been a gradual decline in Russia engaging with nations far from its border. In the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia was slow to engage with nations even right at its border. This trend shows general Russian diminishment in engaging with global or regional issues. Russia’s eventual involvement was due to Turkey’s involvement with the issue. Although Russia has engaged less on the world stage, it still considers itself a regional leader and doesn’t take kindly to others encroaching in this area of is influence. Turkey’s involvement is especially tricky for Russia because Turkey is a long term player in the Russian neighbouring regions that is likely to continue to indirectly engage Russia.

In Belarus, although Putin’s path to take advantage of the situation and reign Belarus back into Russia’s sphere of influence was easy, it sheds some light on past Belarusian actions before the protests. As mentioned earlier, Belarus was becoming friendlier with Western countries in the EU Bloc and Putin was unable to do much about it. The rigged election and ensuing protests offered Putin a chance to reign in Belarus, however, had the protests not happened, Belarus would like have continued to seek closer ties with the West. This demonstrates the frailty of Russia’s relations with its neighbouring states as well as their unwillingness to commit to Russia’s influence.

Although Russia has seen successes with both Belarus and Nagorno-Karabakh, it is plausible that as time goes on, Russia will recede further away from regional conflicts. A possible reason for this is Russia’s economic state which has deteriorated with years of sanctions and over dependence on specific economic sectors. Hence, Russia’s economy could be heading to a point where it is unable to power the sprawling state infrastructure, namely the military which helps Putin project power.

Connection to Primary Texts

This section explores the connections between two primary texts and events revolving around former Soviet states in the second half of 2020: “The End of History” by Francis Fukuyama and Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin.

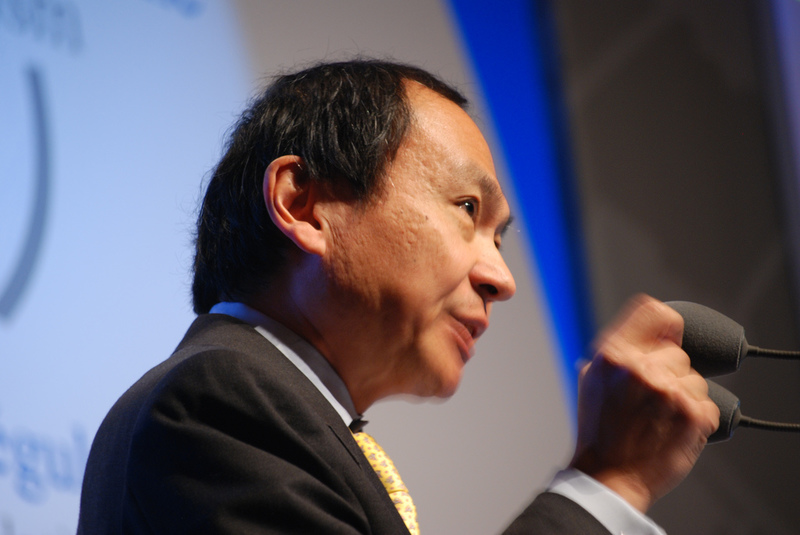

The End of History by Francis Fukuyama

In “The End of History” Fukuyama proposes that all nations and governments are inevitably headed towards a governance form of liberal democracy. He contends that the biggest threat to this gradual progression was communism being exported during the Cold War but that since the US has won the Cold War, it is no longer a threat. The situation in Belarus would tell us otherwise. As mentioned before, one of the reasons that Russia doesn’t want Belarus to undergo a democratic revolution is that it would bring democracy too close to Russia’s borders. Russia itself is not a democratic country. As such, the current events taking place Belarus offer an insight into what Fukuyama predicted almost 30 years ago. In one way, Belarus solidifies Fukuyama’s assertion that as time goes on, the liberal democracy ideology spreads to all countries as it has arrived in Belarus. Yet, in another way, Belarus shows that with the existence of countries like Russia, liberal democracy may never encompass the entire world, in fact its spread will be stopped and perhaps even reversed as is currently taking place in Belarus. Fukuyama didn’t necessarily lay out a timeline for when liberal democracy should have spread throughout the globe. However, one of his arguments is that the Cold War and the USSR’s exportation of communism was a major threat that has been defeated. The events in Belarus show that Russia is still capable of exporting a non-democratic, if not necessarily communist form of governance. Perhaps the USSR Cold War ideology isn’t entirely gone, rather it has morphed from spreading communism to keeping the spread of democracy away from Russia’s neighbouring regions. This still, however, contradicts Fukuyama’s predictions for universal liberal democracy.

Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin

In Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin, Sorokin draws on history to create a technologically advanced future Russian state known as “Rus” where freedom of speech is curtailed and one figure has dictatorial control of all of Rus. This can be inferred as both a reflection on Russia’s past as well as a warning of what its future may hold. Sorokin’s Rus has similarities to the USSR before the 80s in terms of dictatorial control and lack of free speech. Sorokin’s novel expresses the fear that the future Russia will return to the same lack of freedom that existed in the USSR. Day of the Oprichnik was written in 2006 when it was becoming evident that Putin was rapidly leading Russia to be a dictatorial state firmly under Putin’s control. Sorokin’s novel at the time would have been received as a warning of the dictatorial transition that Russia was undergoing. Years later, we can see that through Putin’s actions that the fears were not unfounded. Through Russia’s relations with former Soviet states it has become evident that not only is Putin suppressing freedom and democracy in Russia but is also controlling its spread near its borders. Putin’s support for Lukashenko in Belarus is undemocratic and driven from fear of democracy coming close to Russia’s borders. Putin’s support for undemocratic regimes draws parallels with the USSRs support for communist movements around the world. Although Russia is not a replica of Sorokin’s Rus, there are evident parallels between Rus, the USSR, and Russia today that point to an undemocratic, suppressed, and negative future for Russia.

Works Cited

- Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History” Francis Fukuyama. Perennial, 1992.

- Sorokin, Vladimir. Day of the Oprichnik. Translated by Jamey Gambrell, Penguin Books, 2018.