RUSS005 - Omeka Project - Nicolas Urick

Power, Persistence, and Punishment in Flux: The Pursuit of Change in Russia and the Former Soviet Satellites

Protest is anything but foreign to the Russian people. The region has a long, tumultuous history of dissent marked by state suppression. Movements of opposition in contemporary Russia have grown since one of the biggest rallies in recent history, during which a performance of Televizor’s “Your Father is a Fascist” sparked a new wave of dissent against criminality in the government. The bands lyrics, “You are afraid to be among the useless” still ring true, as dissent in the region has become complicated by growing acquiescence to authoritarianism amongst the citizenry.

Today, two categories of protest and civil dissent are most prevalent in Russia and the former Soviet satellites. Protests in "Category 1" focus on the organized opposition to institutional maladies and the choices of specific powerholders, while movements in "Category 2" address systemic issues by rejecting their underlying oppressive power structures.

Oppositional movements structured around the breakdown of the consent to be ruled (Category 2) have been most effective in cultivating popular support for constructive change in the region, though the dynamic is constantly in flux.

Category 1: Protest and Dissent Centered on the Organized Opposition to Institutions and Power-Holders

Before delving into the complexities... What is "Category 1" of protest and civil dissent in contemporary Russian Society?

Select movements within the “Protest and Civil Dissent” node focus on the organized opposition to institutions and the choices of power-holders. The protestors in “Category 1” tend to address the ways that larger systematic issues appear in society, rather than their roots in an imbalanced power-dynamic. These pursuits of dissent function with an implied “power-over” dynamic, in which rulers are still recognized as holding indomitable power and the people are considered weak. Demonstrators in "Category 1" protests attempt to change the decisions of the current power-holders in hopes of gradually effecting change in larger institutions.

Protests in “Category 1” are distinctly influenced by the socio-political landscape of Russia, as they largely work within the paradigm of change promoted by the state. These protests provide insight into the nature of suppression and oppression in Russia and the contemporary state of free speech in the greater region.

Notably, the four protest movements explored here focus on either long-term dissent or protest based on symbolic art. This dynamic is in line with the tendencies of these protestors to emphasis message-delivery rather than a challenge of greater power structures.

How Does the Marginal Efficacy of Protests in "Category 1" Today Speak to Suppression and Oppression in Russia?

The protests detailed by Meduza in “Sorry We Exist—The Emergence, Blossoming, and Almost Complete Defeat of Russian Drug Activism” and “Off the cross and into the police van" - ‘Meduza’ speaks to the activists behind the ‘crucifixion’ outside Moscow’s FSB headquarters” provide insight into the oppression of marginalized groups and the systematic suppression of dissent in Russia. The articles, which focus on the twenty-eight-year history of drug activism in Russia and the movement against political-imprisonment by the FSB, respectively, follow the continual suppression of dissent both by power-holders and the members of society whose inaction maintains authoritarian power dynamics.

The history of drug activism in Russia has focused on the integration of marginalized voices into the current socio-political apparatus, rather than the breakdown of the powers that create oppressive health-care conditions . This method of protest has proven futile, as dissent is able to be suppressed not only by power-holders themselves, but also the tools they employ, such as riot crews and public servants tasked with cleaning up protests. With little effort to dismantle this oppressive apparatus, the protestors have yet to achieve measurable change. While the drug-activism movement progresses towards creating more equitable conditions, their campaigns ultimately encourage acquiescence to authoritarianism by operating largely within the confines of the governmental avenues of change.

"Our deaths are our shame"

The main slogan for the FrontAIDS movement

Similarly, Pavel Krisevich’s symbolic protest of the FSB’s political imprisonments displays how the imbalanced power dynamic between the police and protestors maintains the authoritarianism of higher level rules. By focusing on art that only questions the isolated actions of the FSB, Krisevich and his allies question specific institutional choices rather than those who enable them. Kriesvich was arrested and his art was removed by police, resulting in a lack of change.

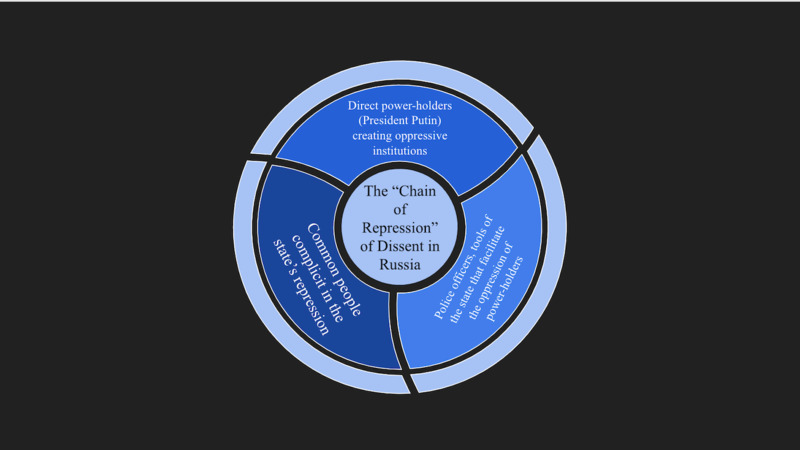

In both stories, a “chain of repression” is maintained, as opposition is silenced not only through the targeted institutions, but through those that uphold them, whether consciously. Not only does protest centered on message delivery fail to create constructive change, but it exemplifies the questionable existence of free speech in contemporary Russia, as voices of dissent are continually repressed.

In the case of Kresvich, his right to free speech was limited even to artistic expression, not dissimilar to the suppressive tactics of the Putin regime. In the movement for equitable drug treatment, those contributing to the marginalization of the affected groups are complicit in their suppression as well. Complicit groups are often conservative factions that objectify drug-users, public servants tasked with dispersing protests, and the larger population that chooses inaction. As this complicity is often passive or pursued for survival, it further evinces the inefficacies of protests that fail to address the imbalance in power and liberate groups unable to act under authoritarian rule.

This dynamic of protest suppression reveals a paradox in protest and civil dissent: While it is important to have a specific institution to demand change within, these movements negate the possibility of larger, paradigmatic change in the oppressive structures of power by working within their very systems of change.

These protests exemplify that while power-holders often funnel oppressive practice through institutions, it is not the institutions themselves nor the power-holders that spread societal maladies in the region; rather, those in power are enabled by wide-spread complacency to suppressive rule. A variety of the Russian citizenry maintains authoritarianism whether through direct support, such as riot-police, or passive acquiescence, often for survival. "Category 1" protests neglect the liberation of these groups by perpetuating the idea that true change is possible within the practices of an oppressive-power structure.

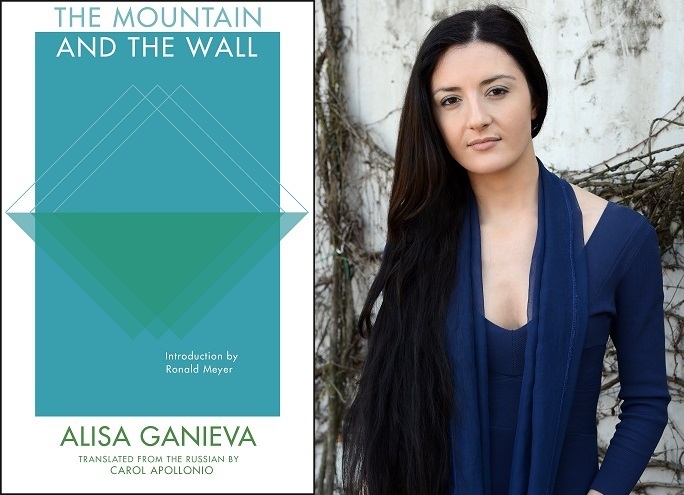

The Mountain and the Wall by Alisa Ganieva and "Category 1" of Protest and Civil Dissent

Alisa Ganieva’s examination of change in Dagestani society in her novel The Mountain and the Wall displays how efforts in opposition to institutions and powerholders in contemporary Russia and the former Soviet satellites are often diminished. Ganieva’s focus on societal divisions via her two protagonists, Madina and Shamil, explores how larger systematic issues spread in society, the contemporary state of free speech in the region, as well as the duality of the human propensity for change.

Madina as a Representation of the Spread of Authoritarianism and the Stifling of Change

Madina, the female protagonist in The Mountain and the Wall, exemplifies the pervasiveness of larger systematic issues in society, especially in terms of how authoritarianism can be maintained through the people. Madina, once Shamil’s fiancée, is overtaken by the spread of religious radicalism in Dagestani society, as she alters her life in conformance to the principles of jihad:

“Madina had stopped hanging out with her old friends in the courtyard; a couple of times someone had dropped her off at home after nine in the evening, and one of the guys on the bench had even seen her out somewhere in a hijab." (Ganieva 90)

Early in the novel, Madina adheres to the institutions enforcing oppressive female gender roles. Her actions do not only support the oppressive narratives of religious radicalism, but they also affect Shamil’s livelihood, displaying the role of the individual in spreading institutional maladies.

Madina’s active indoctrination into oppressive, radicalized religious practice in Dagestan persists, culminating in her violent support of the ruling armies: “Madina passionately supported the calls for violent action; she knitted warm socks and sweaters for jihadists and was prepared to share everything she had with the umma” (236).

Madina’s gradual consumption by oppressive institutions displays how individuals uphold authoritarian rule, a key aspect of “Category 1." Her personal actions first extend the rule of oppressive institutions into her home and ultimately result in violent actions that promote the spread of authoritarianism.

Madina thus displays that individual choices are quintessential to the maintenance of authoritarian rule. Madina’s role in The Mountain and the Wall speaks to the chain of repression in the story of Pavel Krisevich, whose symbolic activism was silenced not only by police officers but also those who cleaned up his protest afterward; both individuals and the state perpetuate the suppression of dissent, though they might do so through different methods. Notably, Krisevich's protest was centered on the freedom of political prisoners; in many ways, Madina can be considered one herself, as her actions "imprison" her in authoritarian practice, whether intentionally.

Shamil and the Role of the Passive Individual in Protest and Civil Dissent

Shamil’s role as a passive protagonist conveys Ganieva’s psychological exploration of the nature of institutional protest and change. As the arguable anti-hero of the novel, Shamil perceives the catastrophes associated with the formation of oppressive institutions around him as if it is normal:

“‘Where is everyone?’ asked Shamil, glancing around the gym.

‘Someone blew up a store down the street—they went out to take a look.’

‘The one that was selling vodka?’

‘Yes, Salman’s, that’s the one. Are you going to work out?’

Shamil scratched his head. ‘I didn’t bring a change of clothes." (93)

Shamil’s lackluster response to a drastic, violent change around him conveys that even extreme events catalyzed by oppressive rule are eventually normalized over time. Shamil’s role in The Mountain and the Wall displays how this normalization of catastrophe encourages the passive individual that perpetuates undesirable rule. Though Madina actively supports the power-holders’ oppressive grasp on Dagestan, Shamil fails to act, enabling the spread of authoritarianism as well.

Shamil’s passivity in The Mountain and the Wall also relates both to the story of Pavel Krisevich and Russian drug activism. Shamil's complicity in the “chain of repression” of voices of dissent in Dagestan is similar to those who cleaned up Krisevich's protest; both contribute to the spread of authoritarianism, regardless of their direct support of the state. The passivity of Shamil also displays the duality of the human propensity for change in drug activism, as his inaction despite opposition to the oppressive power-holders in Dagestan shows that the risk of change often overpowers the perceived benefits thereof.

Shamil represents Ganieva's exploration of acquiescence and passivity in stifling protest and civil dissent in Russia and the former Soviet Satellites

Category 2: Protest and Dissent Centered on the Breakdown of Consent to be Ruled

Before delving into the complexities... What is "Category 2" of protest and civil dissent in contemporary Russian Society?

Select movements within the “Protest and Civil Dissent” node focus on the breakdown of consent to be ruled by a broader oppressive entity. “Category 2” differs from “Category 1,” as it encompasses protests that address the root of societal and institutional issues, rather than their isolated appearances.

Protests in “Category 2” intend to break down or significantly alter the current power dynamic. Though these movements often respond to certain events, they address the roots of the event beyond its mere negative effects. These protests tend to be more spontaneous, widespread, and noticeable, typically in the form of public marches.

The articles in “Category 2” mostly concern protests against the dictatorial Lukashenko regime in the former Soviet satellite, Belarus. These protests address the efficacy of non-violent action in the broader region, the formation of historical narrative, and the nature of the oppressive tools of the state. Relative to the protests detailed in “Category 1,” these protests harness greater power in encouraging revolutionary spread and increasing the human propensity for change.

How does the increased efficacy of protests in "Category 2" relate to the historical connections between Belarus and Russia and their approach to dissent, the destruction of oppressive institutions, and the role of human ingenuity in creating change?

The articles “Meet the Belarusian developer working on a facial recognition algorithm for doxing riot police” and “The Slavic brotherhood’s future Belarusian security expert Yahor Lebiadok breaks down military cooperation between Moscow and Minsk,” which discuss methods of non-violent action in the region and the reaction of President Putin to protests in Belarus respectively, explore the state's suppression of dissent, the relationship between Russia and Belarus, and the heightened ability of "Category 2" protests to create constructive change and influence the formation of historical narrative.

The article focused on the methods of non-violent direct action addresses the inefficacies of protests in “Category 1,” as it shows that attacks on institutions are only meaningful when they address their roots in oppressive power-structures. As Lukashenko uses the riot police to suppress dissent, protestors targeted them by releasing their personal information online, causing thousands to quit. This move was not in opposition to police themselves, but rather their role in the regime's authoritarianism. This more comprehensive praxis effectively eroded Lukashenko's capacity to suppress dissent, as evidenced by the increased size of protets.

The article on President Vladimir Putin's response to the protests against the rule of President Lukashenko explores the nature of "Category 2" protests via the historical, political, and economic links between Russia and Belarus.

Despite deaths, destruction, and police brutality occurring en masse throughout the protests in Belarus, the first aspect of the movement labeled a “turning point” was the support of President Putin for the maintenance of Lukashenko's power, based on the historic economic interdependence of the two countries.

The dynamic between Russia and Belarus contributes to the distinct nature of protest and civil dissent in the region, as their historical interdependence creates a mutual distaste for change among power-holders, placing demonstrators under heightened suppression. The narrative of support between Moscow and Minsk further emphasizes that merely targeting oppressive institutions and choices of powerholders will fail to create meaningful change, as the power structures necessary for the continuation of these institutions are long-standing and span borders.

Protests in “Category 2” of the analytical framework of protest and civil dissent speak well to the viable forms of effecting change in Russia and the former Soviet Satellites, as they display that only through the breakdown of consent to be ruled by an oppressive entity can the destruction of repressive and supressive institutions truly begin.

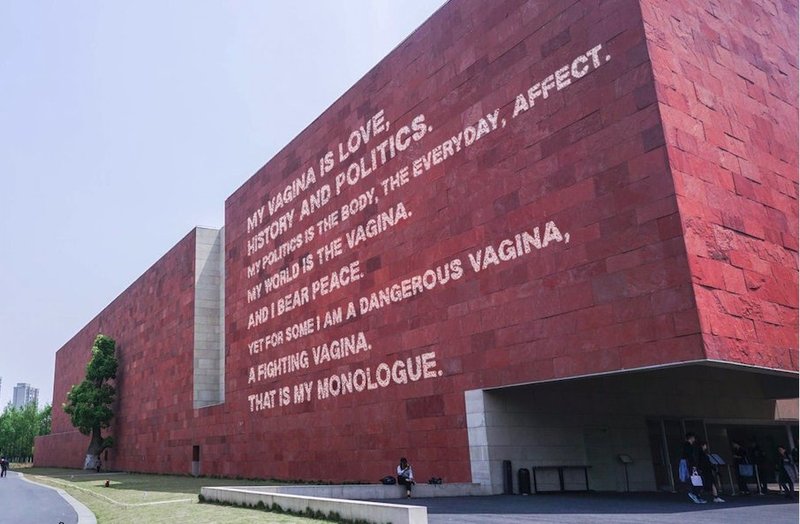

Galina Rymbu's “My Vagina" and Category 2 of Protest and Civil Dissent

Galina Rymbu explores protest and civil dissent in Russia as it relates to the ecological connections between the individual and political "bodies." The articles analyzed for the node reveal that the destruction of oppressive institutions, as described in “Category 1,” can only come from the prior breakdown of the consent to be ruled by an oppressive force (Category 2); Rymbu’s focus on the relationship with the corporeal conveys that this breakdown must begin with the radicalization of the individual body.

The interconnectivity framework of Rymbu’s poetry sheds light on the nature of protest and civil dissent in Russia, as her work not only directly represents a form of protest art, but more broadly speaks to the spread of revolutionary spirit from within.

"My Vagina" and The Radicalization of the Body as the Basis of Breaking Down the Consent to be Ruled

Rymbu’s “My Vagina” speaks broadly to the breakdown of consent to be ruled by an oppressive force via empowering imagery of her female corporeality and its relationship to the political “body.” Rymbu first writes directly of this relationship:

“I didn’t know that everyone had an interest in my vagina: / the state, my parents, gynecologists, strange men.” (Rymbu 44-45)

Following this establishment of the dynamic between her femininity and most notably the state and men, Rymbu details imagery that prescribes archetypal feminine experiences to her husband:

“I love it when your penis is covered with my blood, / and love to imagine that you’re also on your period / ………… in my dreams, you might someday carry our daughter” (64-65, 77).

Rymbu’s imagery draws a further connection between the cultivation of greater political change and the individual body; as she first mentions her vagina as a subject of scrutiny from men and the state, and then prescribes traditionally feminine traits to her husband, she suggests that it is through physical empowerment (or, perhaps, recognizing a lack thereof) that the body is radicalized and inspires change. Likewise, her connection of her husband to the patriarchy addresses the complicity of otherwise 'innocent' individuals in maintaining oppressive power dynamics.

The connection of the male genitalia to a typically female birth suggests the figurative "birth" of a new, transcendent society that defies gender constructs; in this way, the body is used as a tool of radicalization that extends to the broader social expectations established by the state.

Likewise, Rymbu’s statement, “To make revolution with the vagina. / To make freedom with oneself” (155-156) conveys directly that the vagina—and the body, more broadly—can cultivate revolution, but only beginning with freedom from within.

As the poem concludes, Rymbu connects the “bodily revolution” to political revolution:

“I think, well, maybe the vagina will bring down this state for real, / drive out the illegitimate president, / disband the government." (157-159)

Rymbu directly discusses the breakdown of the consent to be ruled—the basis for “Category 2” of protest in Russia—and asserts that movements of dissent are most viable when they cultivate power from within.

Rymbu's poetry aligns with the conclusions of the articles in "Category 2," as they both assert that one must start at the “root” of societal issues—the body and the consent to be ruled, respectively—to create larger institutional change.

Furthermore, while the article about Moscow and Minsk asserts that only those involved in the inner-workings of the state can create change, Rymbu suggests that these intricacies of the state are dependent on individual bodies, and it is through personal radicalization that they will adjust.

The imagery of Rymbu’s husband also connects to the article detailing the facial recognition technology that doxed police officers, as it suggests that the dismantlement of oppressive power structures is most effective when it addresses the livelihood of complicit individuals. Rymbu’s “My Vagina” speaks adequately to the most effective catalysts of protest and dissent in contemporary Russia.

In Short—What Can We Take From The Exploration of Protest and Civil Dissent in Contemporary Russia and the Former Soviet Satellites?

Protest and civil dissent in Russia and the former Soviet Satellites is an enigmatic phenomena that challenges who is in power, why they are in power, how they maintain that power, and how that power can be dismantled.

The Mountain and the Wall and Galina Rymbu's poetry explore the viability of creating societal change via the destruction of oppressive institutions and the breakdown of the consent to be ruled respectively, as both convey how dissent spreads and is stifled in contemporary Russia.

While the future remains unclear, Galina Rymbu's words in her poem "Untitled" introduce promising possibilities for protest and civil dissent in the region, as she expresses that the drive for change is intrinsic to oppressed populations and has the power to spread like “FIRE! FIRE! FIRE!”(9). Rymbu's verse suggests that as the ordinary people are the root of state power, the radicalization of the body will bring change to the forefront of the collective mind and create the possibility of greater societal revolution.

While protest focused on the breakdown of the consent to be ruled (Category 2) seems to triumph in efficacy today, the fluidity of movements of dissent in the region are clear from the exploration of the node, and will undoubtedly develop with alterations in the unique socio-political landscape of Russia.

Works Cited

- Arlie, Genevieve. “Bullet in My Mother Tongue: An Interview with Alisa Ganieva.” Asymptote Blog, 30 July 2015.

- Denyer, Andrey, and Jørn Holm-Hansen. “Dagestan.” Store Norske Leksikon, 4 July 2020.

- Dubrovsky, Nika. “‘My Vagina’ By Galina Rymbu — Public Art by TheYesWomen Group.” Twitter, Twitter, 4 July 2020.

- Ganieva, Alisa, and Ronald Meyer. The Mountain and the Wall. Translated by Carol Apollonio, Deep Vellum Publishing, 2015.

- Homoatrox. “Protest Rally against Lukashenko, 30 August 2020. Minsk, Belarus.” Wikimedia Commons, 30 Aug. 2020.

- Leschina, Sergey. “Alisa Ganieva at the MIBF 2018.” Wikimedia Commons, 9 Sept. 2018.

- Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation. “Русский: Радиолокационная Станция «Волга».” Wikimedia Commons, 9 Oct. 2015.

- Press Service of the President of Russia. “Vladimir Putin and Aleksandr Lukashenko, BRICS Summit 2015.” Wikimedia Commons, 8 July 2015.

- “A Reading with Galina Rymbu and Helena Kernan - Pushkin House's First Contemporary Russian Poetry in Translation Residency.” Pushkin House, 13 Mar. 2020.

- Rymbu, Galina. “My Vagina.” Translated by Kevin M.F. Platt, n+1, 2 Aug. 2020.

- Rymbu, Galina. “Untitled.” Translated by Johnathan Brooks Platt, n+1, 2 Dec. 2018.