RUSS005 - Omeka Project - Annie Zhang

The Price of Power: Pitfalls and Possibilities for the Contemporary Russian Economy

Introduction

“We are stuck half-way, having left the old shore; we keep floundering in a stream of problems which engulf us and prevent us from reaching a new shore.”

Boris Yeltsin, speaking about the painful transition from a planned to a capitalist economy in his 1997 state of the nation address

The past 30 years in Russia have been marked most significantly and visibly by economic change. In 1986, Gorbachev began implementing the economic policies of perestroika (i.e., restructuring), which marked the beginning of the end of Soviet-style central planning and command economy. In the early 1990s, inheriting the mandate of economic change from Gorbachev, President Boris Yeltsin attempted to rapidly convert the faltering Soviet controlled economy into a market economy. This “shock therapy” produced dismal and uneven results. Pushback from conservatives in the government meant that Yeltsin was unable to make complete reforms; oligarchies in key industries proliferated, while Russia's farmers faltered due to entrenched beliefs in collectivization. Rising social unrest propelled by organized criminal activity and corruption set the stage for Putin’s election in 2000.

The “new shore” Yeltsin speaks of in the above quotation represents the economic dream of the past 30 years in Russia: the unmet Soviet promise of a good life finally fulfilled by the structures of a market economy. Has Russia reached this new shore under Putin?

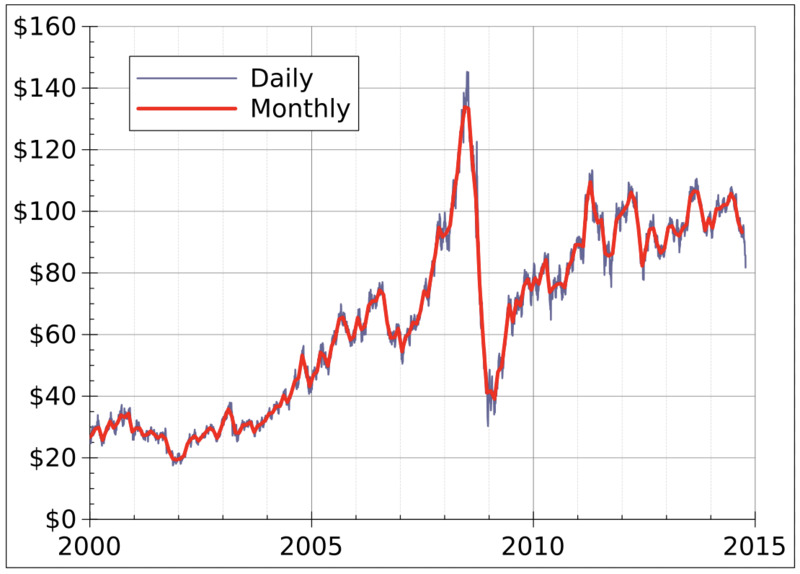

Perhaps the greatest and most shocking change Putin has wrought is that of the economy. Putin’s sweeping reforms to Russia’s economy have stimulated growth far beyond the wildest dreams of his predecessors. The above graph demonstrates how Russia's GDP has grown every year since Putin took power. As the economy grew , it became increasingly centralized. Now, most economic decisions are delegated to the federal government; regional governments have very little fiscal independence. Many believe that it is this command structure that has propelled the growth of the past twenty years. However, the image of economic progress driven by Putin’s centralized control is an illusion that has been propped up by inherent features of the Russian economy. The centralization of control has created a trade-off; economic stagnation is accepted as long as Putin can project an image of economic and political strength. Reaching the 'new shore' sought by Yeltsin may remain an impossibility until structural economic change is achieved through political opposition.

An economy for the people or for the state?

[W]ithin this period, there has only been one positive thing, if you leave aside the trivia. And that thing is the price of oil and natural gas.

Nikolai Leonev, retired KGB lieutenant-general, speaking about Russia's economic development under Putin's presidency

The structure of the contemporary Russian economy is most heavily influenced by how the Putin administration's authoritarian tendencies bleed into its economic policies and priorities. The administration capitalizes upon inherent features of the Russian economy to centralize economic and political power at the expense of maximizing growth and raising living standards.

Inherent features of the Russian economy coinciding with favorable global conditions drove much of the economic growth during Putin’s regime. The first, and arguably the most important, inherent feature is the economy’s reliance on oil and gas production. Russia contains the largest natural gas resources in the world. Putin came to power at a time when global oil and gas prices were surging, as evidenced by the above graph. It is estimated that as much as one-third to one-half of the growth rate in Putin’s first decade is due to a rise in oil prices. The ruble (Russia's currency) was also devalued in 1998—a process which lowers the cost of exporting for domestic companies, stimulating GDP growth. Neither the devalued ruble, nor the rise in energy prices were controlled by Putin; any leader would have inherited the economic growth potential of these inherent features.

The growth potential of Russia's oil and gas reserves has shaped the structure of the Russian economy. The bulk of Russia's energy sector is now controlled by the state, which was partly accomplished by the replacement of oligarchs like Mikhail Khordovsky (who was jailed) with Putin's close associates at the heads of formerly privately-owned companies. Marshall Goldman, Associate Director of the Harvard Russian Research Center, used the term "petrostate" to describe Russia's reliance on and control of oil and gas revenue. State control of the energy sector has resulted in the concentration of revenues and political power to the central government in Moscow.

The Great Recession slowed the wave of economic success that Russia rode throughout Putin's first presidency, yet could not dismantle the centralized economic structure. As global energy prices and foreign investment in Russia dropped, so did incomes, spending, and production. Since 2008, Russia's share of global GDP has continued to decrease. This indicates that Russia's growth lags behind that of other countries. The economy is fairly stable due to the establishment of "rainy day funds," but it is no longer growing; incomes have barely changed since the 2000s. Despite Russia's slowing growth, the government has been slow to enact reform policies. Why? There is no realistic way to restart growth other than by decentralizing and opening up the economy. As it is the centralized economic structure from which Putin derives his power, further economic stagnation is almost inevitable.

The story of the Great Recession demonstrates that it is no longer economic growth that keeps Putin in power, but the economic structure. The centralized structure of the economy makes it particularly vulnerable to external shocks, of which the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is a prime example. The economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the most unsustainable aspects of the economic structure.

“Putin... proceeds from the fact that almost the entire economy is state-owned. Budget employees + employees of state-owned companies + employees of large controlled companies. They will be paid a salary. The rest - all sorts of designers, lawyers, taxi drivers, waiters and so on can be sacrificed.”

Alexei Navalny, speaking about the state's failure to provide adequate stimulus measures, 4 April 2020, Twitter

Petrostate Politics

As a petrostate, Russia is especially vulnerable to changes in global energy prices, which were heavily impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. The thing to understand about prices, especially energy prices, is that they are dependent on demand. Due to lockdown measures, global demand for oil and gas dropped. In September, vaccine setbacks and the increasing number of cases in Europe created financial distress in Russia. Energy revenues dropped, which constrained the government’s ability to create extrabudgetary spending for stimulus packages. Furthermore, inflow of international capital dried up as investors were swayed by the gloomy prospects for a quick recovery from the pandemic. Russia already has a difficult time attracting international investors, who are cautious due to the corruption and stagnation that plague the economy. The IMF estimated that as a result of the pandemic's impacts, Russia's overall GDP will contract by four percent this year. This number is dependent on stimulus measures, which will be discussed below.

Budgetary Centralization

Putin’s economic policies have centralized the revenue system, which limits the power of local governments to address residents' specific needs and promote regional development. The majority of regional tax revenues are first transferred to the federal government, which then transfers them back to the regions in the form of subsidies. The regions' fiscal dependence is transformed into political dependence in two ways. First, regions that are politically close to Moscow receive more transfers. Second, regions that default on debt are subject to government takeover and additional controls. Reduced independence has led to unequal development between regions and recurring regional debt crises.

The pandemic has imposed additional costs on regional budgets, necessitating extra spending to boost healthcare infrastructure and stimulate consumer spending. Due to budgetary centralization, very few regions had excess reserves to draw on during the pandemic. Therefore, many regions were forced to borrow money from the federal government to meet healthcare and stimulus costs. Regions that default face government takeover.

Budgetary centralization exemplifies the centralized structure of the economy. Regional debt issues further highlight the tradeoff between stagnation and economic and political stability. The central government claims that its budgetary system ensures equality between the regions and fiscal responsibility, yet the system stifles regional economic development. The subsidies and government loans are projected to be the solution to regional economic issues when they are in fact the root of the crises.

Aversion to Social Spending

The government’s unwillingness to relinquish central command of the economy has also resulted in uneven and insufficient stimulus measures during the pandemic. Though the government promised bonus payments to medical workers, medical workers across Russia have reported not receiving bonuses at all or receiving reduced amounts. The bonuses were part of a larger package aimed at providing stimulus for both medical workers and small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs). The rollout of stimulus for SMEs was just as uneven as that for medical workers. Ombudsman reports from May stated that just under 10% of SMEs were actually able to access stimulus benefits. Furthermore, the total value of stimulus packages was significantly lower than those in the United States and Europe. The government’s reluctance to provide stimulus on par with those of other similarly-sized countries despite the existence of funds in the National Wealth Fund can be traced back to the maintenance of political control.

In Russia, as in other petrostates, the creation of "rainy day funds" meant to reduce the direct effects of changing oil and gas prices on the economy are crucial for maintaining economic stability. However, reliance on the stability these funds provide also hold governments back from diversifying the economy. In Russia, the concentration of revenues to the central government is mainly achieved through the maintenance of the National Wealth Fund. Revenues are stored in the Fund if oil and gas prices are above a certain level. The National Wealth Fund can be drawn from as long as its value is over 7% of Russia’s current GDP. The central government determines how much is withdrawn and where excess revenues are spent.

The central government has so far refused to withdraw from the National Wealth Fund to support stimulus spending. The government’s key narrative is that saving rather than spending is crucial to protect Russia from outside threats; the National Wealth Fund is used to project an image of economic and political stability. However, the authoritarian impulse to prioritize outside threats over pressing domestic concerns has led to a dismal domestic economic situation, particularly for Russia’s poorest peoples and regions.

"Strategically important firms" vs. small business

The impact of lockdowns demonstrates the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic in Russia due to centralization around state-owned firms. As the above section notes, small businesses did not receive sufficient stimulus measures. The government also paid lip service to keeping small businesses open while simultaneously making it impossible for them to generate enough revenue to stay open. During the second wave of the pandemic, Moscow decided to keep businesses mostly open, in contrast to the full lockdowns implemented during the first wave. Moscow governor Sergey Sobyanin also ordered businesses to keep thirty percent of their staff on remote work. However, this presented trouble for small businesses, such as restaurants, where working remotely was impossible.

This move stands in stark contrast to the government's support of "systemically important firms," or large companies considered to be crucial to Russia's economy. Many state-owned enterprises are designated as systemically important firms. These firms have automatic access to low-interest loans and tax breaks, whereas Russia's SMEs have to navigate impossible restrictions and regulations to access the same.

Instead of increasing financial support to people and small businesses through stimulus measures, the government eased restrictions. Easing restrictions undoubtedly amplifies the public health crises caused by the pandemic, yet this was seen as an acceptable trade-off in order to protect the government’s savings. As ordinary Russians dig deep into their savings during the pandemic, the central government holds tightly to theirs to maintain their ability to project political power.

Growing Inequality

Finally, the healthcare impacts of the pandemic illuminate the growing class divides in Russian society. Under Putin, income inequality in Russia has grown severely. During the second wave of the pandemic, hospitals, doctors, and patients across Russia scrambled to procure coronavirus treatments. While the wealthy splashed out for extravagant and costly treatments, poorer citizens and regions were left empty-handed by the central government, which struggled to organize deliveries from international pharmaceutical companies. The fiscal and political dependence of the regions is crucial here. In Dagestan, one of Russia's poorest and most remote regions, the leadership attempted to procure needed medications from Moscow, but it was determined that since Dagestani mortality rates were low, medications weren't required. This is perhaps the greatest economic failing on the government’s part, but it is also the most expected. Regions are expected to fend for themselves on matters like medication procurement despite having most of their revenues tied up at the central level. The divide between the poorest and richest regions is sure to increase during the pandemic. Budget specialist Alexandra Susina remarks that “It’s almost like the politicians want to keep people poor so that all of their energy is focused on surviving, leaving no time to protest." For the Putin administration, the maintenance of economic control is clearly crucial to the maintenance of political control.

Putin’s authoritarian control of the economy and his leveraging of natural resources as a political tool leaves Russia open to economic sanctions from foreign governments and invites distrust by investors who suspect that corruption and state interference will result in poor returns. However, any “outside threats” the government seeks to combat are really due to the government’s own making. Russia's unpredictable and illiberal behavior on the world stage improves Putin's domestic popularity because it can be construed as self-defense against Western countries which seek to undermine Russia, yet it also threatens Russia's position in the global economy.

The latest example of this phenomenon is the poisoning of Alexei Navalny, a prominent critic of Putin. Navalny is an outspoken advocate for market reform and the revitalization of an economy that works for the people. The Navalny poisoning cast a shadow over on the Nord Stream 2 project, a gas pipeline that is being built to transport Russian gas to Germany without crossing through Ukraine. For Putin, gas is a geopolitical and geoeconomic tool. Yet the Russian economy also survives on gas, meaning that if Germany pulled out from the project due to the Navalny poisoning, the economy would take a sharp hit. Illiberal tactics like the Navalny poisoning provide opportunities for the domestic and international projection of political power at the expense of Russia’s pure economic interests.

How Does Contemporary Literature Speak to the Economic Situation?

The long arm of the economy reaches into every aspect of citizens’ lives, from lockdowns to the wealth gap. Contemporary literature discusses economic issues from two key perspectives. First, regional perspectives on economic issues are used to build the social setting of a novel. Second, literary subjects discuss the economic situation directly as a form of criticism or satire.

The Mountain and the Wall

In Alisa Ganieva’s novel The Mountain and the Wall, critical economic problems help to build the social backdrop for the setting of the novel. The Mountain and the Wall illuminates the hypothetical possibility of the Russian government constructing a wall between the Caucuses regions and the rest of the country. The earlier discussion of budgetary centralization and regional debt crises speaks to the conflict between the regions and the central government alluded to in the novel.

In the novel, the characters discuss the situation of regional subsidies from the central government.

“What’s it like in Moscow?”

“Anyone with any brains is scared, Shamil, and fools are celebrating. They think that they’ve solved all their problems, that by stopping the subsidies they’re saving money. But have we ever seen any of those subsidies here? My village did everything on its own, installed plumbing, built a gym—and they did it at their own expense, with their own hands. All they got from the central government was excuses, and not a single kopeck…” (Ganieva 166)

The novel undermines the central government’s narrative surrounding its regional economic policies by highlighting the inefficiency of government transfers and the illusory burden Moscow bears in making these transfers. Putin’s economic policies collect regional revenues for the central government so that they can be redistributed to the regions. However, the characters note that these transfers are ineffectual and provide no substantial economic benefit for the region. The nonsubstantial nature of these transfers makes Moscow’s burden in making these transfers similarly illusory. There is no real need for the centralization of the budget; it only serves to make the regions politically and economically dependent on the central government. The novel highlights the fact that the inefficiency of the transfer system is not due to the economic needs of the poorest regions, but is instead due to the centralization of the budget process. Centralization allows bureaucratization and corruption to bleed money from the system. The poorest regions are still left underserved, while the wealthiest regions complain that their revenues are being taken from them.

The economic issues surrounding regional transfers serve as the basis for the plot of The Mountain and the Wall, which goes on to discuss further issues of religion and culture in the Caucasus.

Day of the Oprichnik

In Vladimir Sorokin’s novel Day of the Oprichnik, a satire that criticizes Putin's authoritarianism, the characters discuss the issue of the Russian economy’s reliance on gas through the device of a play that occurs within the novel. The play satirizes the way the government leads citizens to think about Russian gas, while the novel as a whole criticizes the control the government has over citizens' beliefs, thoughts, and even their bodies.

In the play, Russian guards protect a pipeline from European thievery. The guards sing: "Europa Gas, that parasite, // For Russian gas must pay!” (Sorokin 99). Sorokin satirizes the dependency of the Russian economy on gas by contrasting the view of gas as a political weapon with the view of gas as an essential cornerstone of the economy. The championing of gas as Russia's source of political power leads the guards to characterize Europe as a "parasite" which consumes Russia's gas. Yet as previously discussed, though gas is used as a geopolitical tool by the Putin administration, the Russian economy would collapse without European demand for gas.

Sorokin also remarks on the unsustainable nature of this dependency. Gas, though profitable, cannot sustain a nation; the national infrastructure–bridges, highways, schools– is severely lacking in comparison to the volumes of gas sales that are made. A character exclaims “You can heat European cities with Russian farts!” (Sorokin 100). Gas is equated to farts–ephemeral, of no real use to the nation's people. In this view, gas generates revenue for the central government and power for the European world, but nothing for the people.

Conclusions

We wanted the best, but it turned out like always.

A "Chernomyrdinka," or popular quote, attributed to Viktor Chernomyrdin, former Russian prime minister

The past thirty years in Russia can be measured quite appropriately by Yeltsin’s metaphor of a shore unreached. Russia has left the old shore of Soviet-style central planning, yet has not reached the opposing shore of a free and functioning market economy. Instead, Putin has entrapped the nation under a form of state capitalism, which generates a broad overlap between the economic and political elite. Though the economic growth that originally drove Putin's popularity is over, Putin's reign over Russia is not. The illusion of Putin's control over the economic growth in the first two terms of his presidency has been transformed gradually into genuine control over the key pillars of the economy, oil and gas firms.

To Putin, the greatest asset in Russia is power, its value derived from how tightly the “national champions," or natural resources, are controlled by the state. Putin first wrote of these national champions in a 1997 doctoral thesis, where he argued that Russia should renationalize its natural resources and then use them to compete globally. These ideas have found fruition in the various instruments Putin utilizes to exert control over natural resources. Control of natural resources forms the broad base from which control over the economic structure is exerted. In effect, Putin’s economic policies force the government to choose between the economic and political elite—the oligarchs—and the common people when it comes to economic crises like the coronavirus pandemic.

A bright spot is that the necessary economic policies are clear. Russia must move to diversify its economy, improve productivity, and combat wealth inequality. These changes are quite intuitive. They are also changes that have been recognized as necessary by the Putin administration for its entire reign, yet they have been impossible to accomplish because of the economic structure which centralizes and ties political and economic power.

The latest shocks to the Russian economy may set forth a new unraveling of political control. Pressures from a resurgent internationalist America under President-elect Biden, increased advocacy by small business, and growing civil dissent all portend a major shift in the economy. It is almost certain that given the links between economic and political control established by Putin, an unravelling of political control will open up avenues for economic change.

Works Cited

- Caledonia558. Yeltsin, Gorbachev, Putin. 30 July 2010. Flickr.

- Doff, Natasha, and Evgenia Pismennaya. “Putin’s Been Stingy With Stimulus Because of Sanction Fears.” Bloomberg.Com, 6 Nov. 2020. www.bloomberg.com.

- Dresen, Joseph F. Petrostate: Putin, Power, and the New Russia | Wilson Center. 2008.

- ---. The Role of State Corporations in the Russian Economy | Wilson Center. 2012.

- Economic Change in Russia | Center for Strategic and International Studies. Accessed 22 Nov. 2020.

- Gaddy and Ickes - 2010 - Russia after the Global Financial Crisis.Pdf. Accessed 14 Dec. 2020.

- Gaddy, Clifford G., and Barry W. Ickes. “Russia after the Global Financial Crisis.” Eurasian Geography and Economics, vol. 51, no. 3, May 2010, pp. 281–311. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.2747/1539-7216.51.3.281.

- Ganieva, Alisa. The Mountain and the Wall. Translated by Carol A. Flath and Ronald Meyer, Deep Vellum Publishing, 2015.

- Guriyev, Sergey. “20 Years of Vladimir Putin: The Transformation of the Economy.” The Moscow Times, 16 Aug. 2019, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/08/16/20-years-of-vladimir-putin-the-transformation-of-the-economy-a66854.

- heycci. English: The GDP of Russia since 1989. Figures in International Dollars Adjusted for Both Purchasing Power and Inflation at 2013 Prices. Figures of 2014 - 2016 Based on IMF Growth Forecasts. 27 Feb. 2015. Own work, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GDP_of_Russia_since_1989.svg.

- IntelliNews, Ben Aris and Ivan Tkachev for bne. “Long Read: 20 Years of Russia’s Economy Under Putin, in Numbers.” The Moscow Times, 19 Aug. 2019, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/08/19/long-read-russias-economy-under-putin-in-numbers-a66924.

- “Russian Economic Sovereignty in the COVID-19 Age.” Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank, 11 June 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/06/russian-economic-sovereignty-covid-19-age.

- “Russian Federation: Staff Concluding Statement of the 2020 Article IV Mission.” IMF, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/11/23/mcs112420-russia-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2020-article-iv-mission. Accessed 14 Dec. 2020.

- Russia’s Growing Dependence on Oil and Its Venture into a Stabilization Fund. http://www.iags.org/n0328052.htm. Accessed 22 Nov. 2020.

- Russia’s Stagnating Economy. https://www.worldfinance.com/markets/russias-stagnating-economy. Accessed 14 Dec. 2020.

- Sorokin, Vladimir. Day of the Oprichnik. Translated by Jamey Gambrell, 2012.

- Staff, Reuters. “FACTBOX: Some Quotes from Boris Yeltsin.” Reuters, 23 Apr. 2007. www.reuters.com, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-yeltsin-quotes-idUSL2331310420070423.

- Thompson Ward - Russia.Pdf. https://moodle.swarthmore.edu/pluginfile.php/586687/mod_resource/content/0/Thompson%20%20Ward%20-%20Russia.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov. 2020.

- Times, The Moscow. “Only 10% of Russian Businesses Have Received Coronavirus Support.” The Moscow Times, 28 May 2020, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/05/28/only-10-of-russian-businesses-have-received-coronavirus-support-a70405.